20:1–21 While ch. 20 is known for the Ten Commandments, |

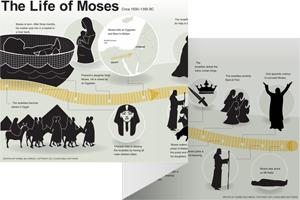

20:2 I am Yahweh, your God The personal name Yahweh (conventionally translated “Lord”) is first given to Moses in Exod 3:13–15, as proof that Moses is indeed sent by God. This statement emphasizes that Yahweh is not to be confused with any other god, and that what follows is to be received as His word alone.

from the house of slaves Yahweh’s deliverance of the Hebrew people out of Egypt is referenced repeatedly throughout the Pentateuch to justify following His commands. Israel’s obedience and commitment to a better society than their neighbors is to be rooted in the memory of oppression.

20:3 no other gods before me Forbids any personal loyalty or relationship with any deity besides Yahweh—the core idea behind the modern term “monotheism.”

Understanding Israelite Monotheism

Understanding Israelite Monotheism

20:4 a divine image Prohibits the worship of any image created, not the creation of the image.

of any image created, not the creation of the image.

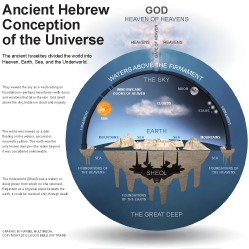

in the heavens above Forbids certain modes of worship. The threefold division in this verse reflects the ancient three-tiered cosmology (see note on Gen 1:6). The “heaven above” tier was considered the divine realm.

20:5 jealous The Hebrew term used here, qanna, denotes intense emotion. It is used elsewhere in the ot to describe extreme zeal or rage (e.g., Num 25:11, 13; 1 Kgs 19:10, 14; 2 Kgs 10:16; Joel 2:18; Zech 1:14; 8:2; Gen 37:11; Deut 29:19; Psa 119:139; Job 5:2).

the third and on the fourth generations Illustrates the concept of corporate responsibility: In addition to the individual being accountable, the community is responsible for the behavior and sin of its members. This passage does not suggest that future innocents will be held morally accountable for the sins of ancestors but refers to the mutual consequences of sins.

20:6 loyal love The Hebrew term used here, chesed, is variously translated as “steadfast love,” “grace,” or “lovingkindness.” It denotes loving favor, and is tied to the covenants. The translation “loyal love” may capture the meaning best. See note on Gen 24:27.

Chesed Word Study

Chesed Word Study

20:7 You shall not misuse the name of Yahweh your God Prohibits hypocritical, insincere, or frivolous use of God’s name. The Hebrew phrase combines the verb nasa (“to take up”) and the noun shawe (“falsehood” or “vanity, uselessness”). God takes personal offense to any affiliation or association with Him that denigrates His character or reputation.

20:8–11 The Sabbath |

20:8 Sabbath The Hebrew word used here, shabbath, relates to the Hebrew verb shavath (which may be rendered “to rest” or “to cease”). The verb can also mean “to observe the Sabbath,” so it is debated whether the verb derives from the noun shabbath or vice versa.

consecrate it See Exod 19:10 and note; 19:14 and note. The holiness of the Sabbath depends on the people remembering and observing it. Since the Sabbath is for the people, it is the people who make it “holy” or “set apart.”

20:10 work The actions that are considered prohibited work are not detailed here but some examples are given elsewhere (16:29; 34:21; 35:3; Num 15:32–36; Isa 58:13; Amos 8:5; Neh 13:15–18; Jer 17:21, 24, 27). Exodus 23:12 elaborates on the positive purpose of the Sabbath rest.

20:11 on the seventh day he rested This rationale for the Sabbath rest connects the Sabbath observer to Yahweh. In Deut 5:15, the rationale for keeping the Sabbath is a remembrance of the Israel’s bondage in Egypt.

20:12 Honor your father and your mother This acts as a hinge between the two categories of the laws (see note on Exod 20:1–21) since it has elements of both divine and interpersonal relationship. The dual focus demonstrates that faith to God was of central importance for the family. This is the only law with an entirely positive message and an offer of reward.

Yahweh your God is giving you Like the book of Proverbs and many other instances of proverbial language in the ot, this promise is not a prophecy. It is a proverb or aphorism—a saying whose general validity is demonstrated by life experience.

20:13 You shall not murder The Hebrew verb used here, tirtsach, describes the unlawful taking of innocent life. One instance, Prov 22:13, refers to being killed by a lion. The ot does not use this verb in connection with capital punishment or war, or when God or an angel is the subject.

Since tirtsach refers only to taking innocent life, the command of Exod 20:13 should not be cited in arguments supporting pacifism or opposing capital punishment. In the ot, the death penalty was established by God prior to the law (Gen 9:6). Thus the law itself did not allow humans to commute a death sentence (see Num 35:31). To take an innocent life was tantamount to killing God in effigy, since humans were created in God’s image (Gen 1:26–27). Protecting an innocent human life showed reverence for God, the primary object of all ot law. |

20:14 You shall not commit adultery The ot regards adultery as sexual intercourse involving a married woman, a man who is not her husband, and mutual consent. It did not consider a married man taking an additional unmarried (or unbetrothed) woman as a wife—i.e., polygamy—to be adultery. Conversely, a woman was not permitted to have more than one husband (polyandry).

as sexual intercourse involving a married woman, a man who is not her husband, and mutual consent. It did not consider a married man taking an additional unmarried (or unbetrothed) woman as a wife—i.e., polygamy—to be adultery. Conversely, a woman was not permitted to have more than one husband (polyandry).

Building Hedges against Adultery Devotional

Building Hedges against Adultery Devotional

20:15 You shall not steal The Hebrew verb used here, ganav, is ambiguous—the object of the theft is not definable. Just as in modern law, punishments for theft in ot laws have varying degrees of severity.

20:16 You shall not testify against your neighbor with a false witness The wording points to a judicial proceeding intended to determine the truth or falsehood of a criminal accusation. The integrity of ancient legal proceedings depended entirely on the validity of witness testimony. The command to be truthful was essential for maintaining a stable society, which required confidence in the court’s ability to render justice.

20:17 You shall not covet The Hebrew verb used here, chamad, does not condemn the general acquisition of possessions or the desire to collect things. It speaks to obsession or a desire so strong that it compels someone to violate another person’s property.

the house of your neighbor Includes any and all of the items inside a house or owned by another household.

20:18 thunder and the lightning Storm imagery is commonly connected with divine appearances in the ot and ancient Near Eastern literature (compare Ezek 1:4–14). Yahweh’s presence is accompanied with storm-god imagery similar to how the Canaanite storm-god Baal might be described. It is rooted in a popular belief in the storm-god, who is known by different names in different regions, such as Hadad in Anatolia, Baal in Syro-Palestine, and Marduk in Mesopotamia. Additionally, these deities are almost always associated with a particular mountain top. This scene in Exodus is one example of Yahweh appearing in ways that parallel storm-gods. The intended outcome of this thunder and lightning is reverence among the people—and it works.

might be described. It is rooted in a popular belief in the storm-god, who is known by different names in different regions, such as Hadad in Anatolia, Baal in Syro-Palestine, and Marduk in Mesopotamia. Additionally, these deities are almost always associated with a particular mountain top. This scene in Exodus is one example of Yahweh appearing in ways that parallel storm-gods. The intended outcome of this thunder and lightning is reverence among the people—and it works.

20:19 You speak with us The people understand Moses as the only person who can approach Yahweh without danger, a point that Moses proved in Exod 19.

20:20 his fear will be before you Moses explains that the thunderous scene has a practical function: to move the people to reverence that inspires obedience. Like the storms of the eastern Mediterranean, Yahweh has the power to destroy, but also to give life. By following or not following the law, Israel chooses which side of this power it will experience.

20:21 very thick cloud See note on 19:9. This is where God resides. Moses is able to enter this space, and speak with him there.

20:22–26 This passage is the transition to the legal corpus often called the covenant code |

20:22 You yourselves have seen The reality of Yahweh’s presence is the basis of the demand in v. 23 (reiterating the first two commands) that Israel worship only Yahweh and make no idols. Other than the phenomena of v. 18 which the people could see, their experience was mostly heard (compare Deut 4:12–18, 36).

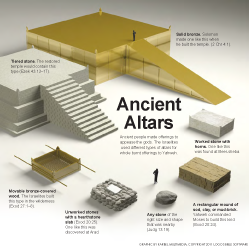

20:24 An altar of earth Describes the kind of altars erected by Noah (Gen 8:20) and the patriarchs (e.g., Gen 12:7, 8; 13:18; 22:9; 26:25; 35:1–7). See Exod 20:25.

erected by Noah (Gen 8:20) and the patriarchs (e.g., Gen 12:7, 8; 13:18; 22:9; 26:25; 35:1–7). See Exod 20:25.

every place There is not yet one location for sacrifice, although that will change with the construction of the tabernacle. However, altars were built after the tabernacle and used in a manner acceptable to Yahweh (e.g., Josh 8:30–31; Judg 13:20; 1 Sam 7:17; 2 Sam 24:25).

20:25 if you use your chisel on it The use of fieldstone rather than quarried stone serves a practical purpose: drainage. Since Israel is not to consume the blood of any animal (Gen 9:4), this is an important feature of sacrificial altars since most sacrifices were consumed, in part, by humans. This also ensures that Israel can set up an altar wherever and whenever is appropriate. Compare Deut 27:5–6; Josh 8:30–31; 1 Kgs 6:7.

20:26 You will not go up with steps onto my altar, that your nakedness not be exposed Prevented someone standing below the altar level from seeing under another person’s garments. In view of the rules for priests’ clothing when serving at the altar (Exod 28:42), this command was likely directed at lay persons worshiping at private altars (v. 24).

|

About Faithlife Study BibleFaithlife Study Bible (FSB) is your guide to the ancient world of the Old and New Testaments, with study notes and articles that draw from a wide range of academic research. FSB helps you learn how to think about interpretation methods and issues so that you can gain a deeper understanding of the text. |

| Copyright |

Copyright 2012 Logos Bible Software. |

| Support Info | fsb |

Loading…

Loading…